Promoting the Moroccan modernity has always been one of the missions Loft Art Gallery has worked for since its opening. If we have exhibited several times the great names of the Casablanca School such as Belkahia, Melehi or Hamidi, this is the first time we are devoting a personal exhibition to the work of Malika Agueznay.

-

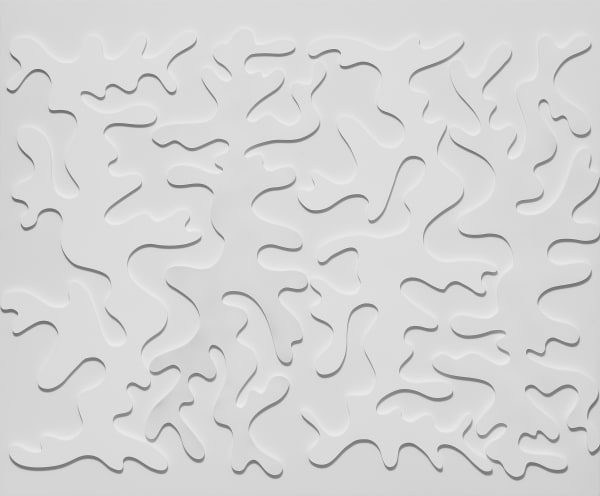

A pioneering artist who took part in Moroccan modernity, Malika Agueznay contributed, alongside the tenors of the Casablanca School, to defining its codes. With them, she questioned contemporary painting and focused her work on the study of forms and pure color. It is she who will develop the most accomplished engraving work within the group and who will defend it each year to new students during the Asilah Festival. Reresearches on the form led her to experiment various media such as wood, which she has been using since her beginnings in 1968. An accomplished painter, sculptor, and engraver, Malika Agueznay pays particular attention to the balance between volumes, surface, and material. The frank colors and repetition give the whole of her work an intense vibration.

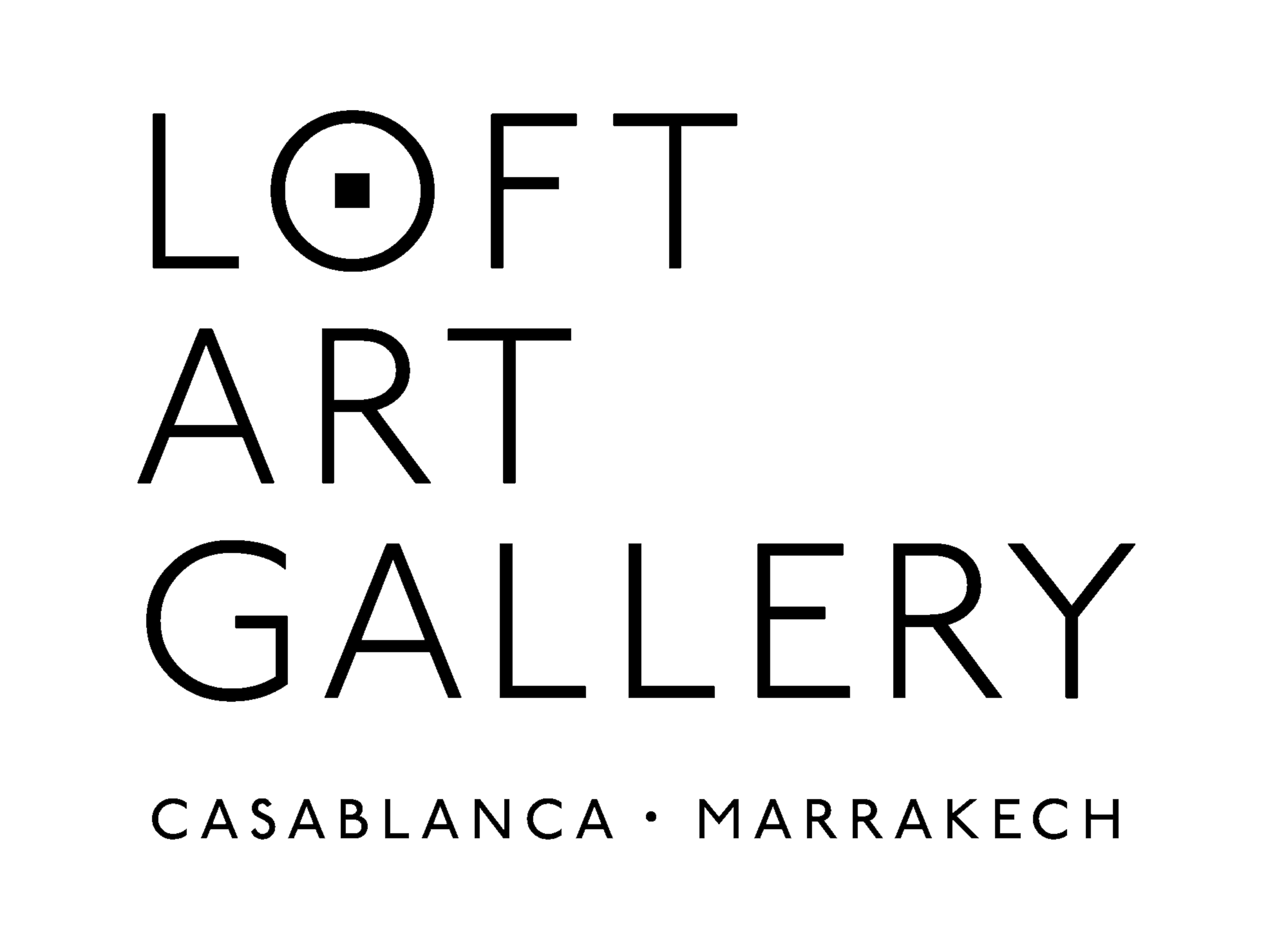

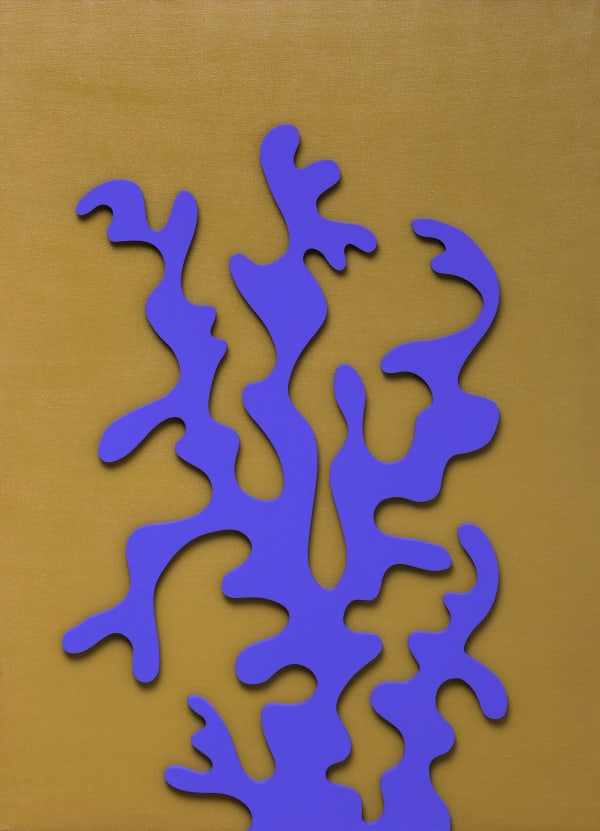

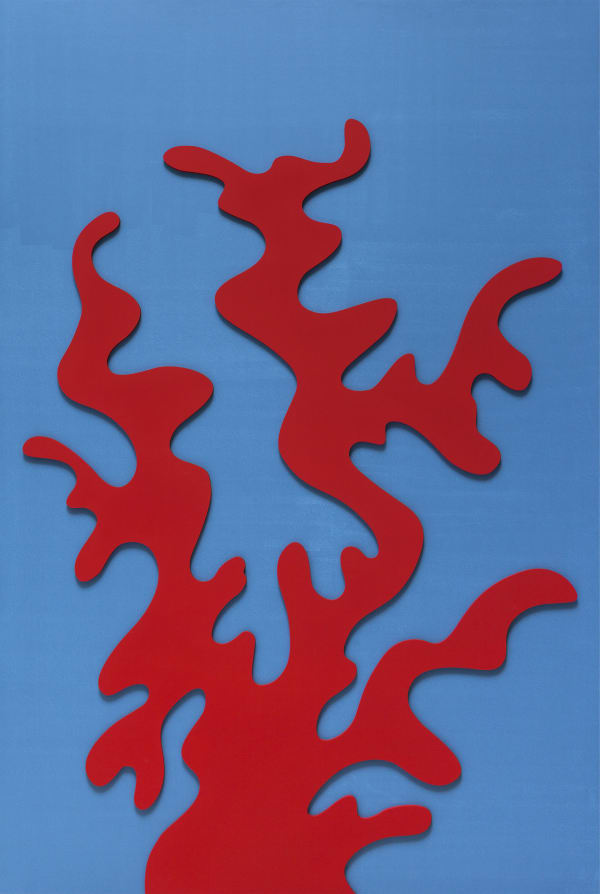

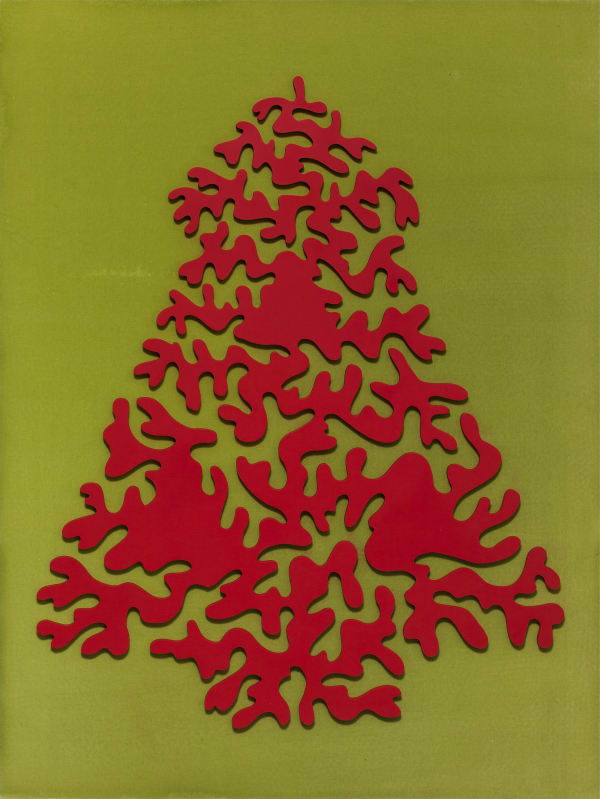

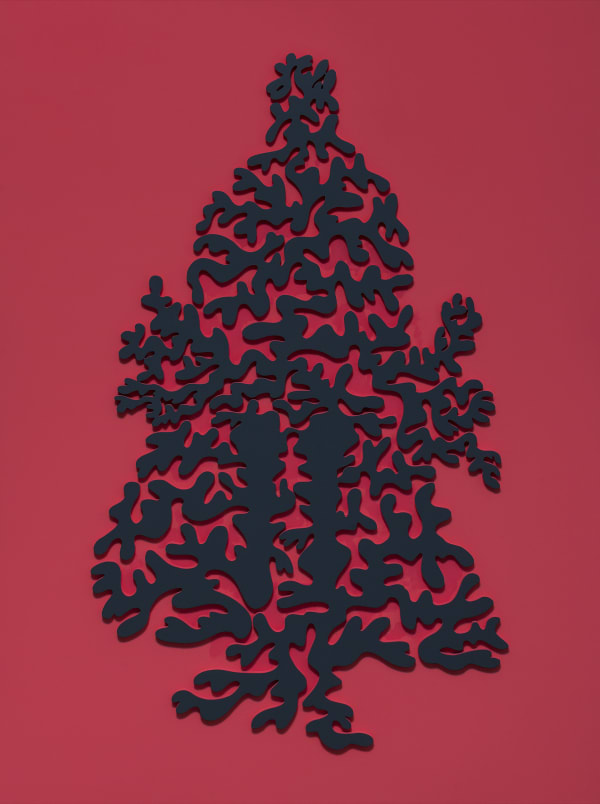

The exhibition offers a look back at her early years when she was a student at the School of Fine Arts and discovered the algae motif that still inspires her today. Through the use of bas-relief as a medium, the exhibition will shed light on the research carried out by the artist since 1968 on this generic form which has nourished her work since its beginnings. This form, which we dare to call algae, and of which each work represents a fragment of a more complete whole that bears witness to a pictorial system chosen and assumed by the artist.

With this exhibition, the gallery wishes to pay homage to the creative power of Malika Agueznay.

-

Can you tell us what made you decide to enroll in the Casablanca School of Fine Arts in 1966, while you were studying science?

I have always drawn since my childhood. I was constantly inspired by nature, with all its colors and shapes. Especially those of plants. My mother in the country used to make country bouquets that I reproduced with my pencils.

When it came time to choose my career path, I preferred the arts to science. That's how I chose to join the Casablanca School of Fine Arts, at a time that I didn't yet know was going to leave a lasting mark on the history of art in Morocco.

-

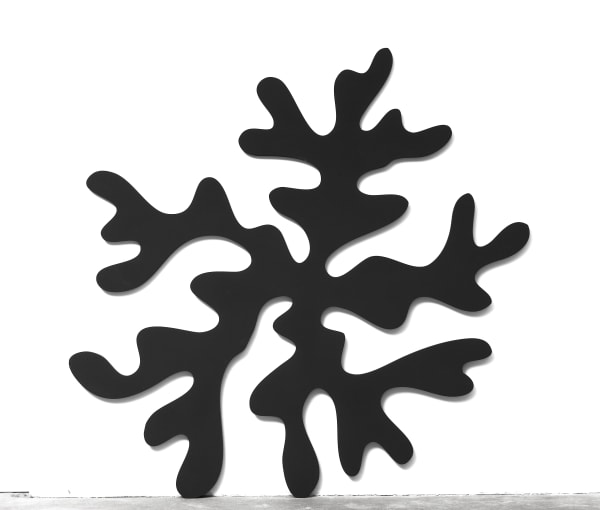

Sans titre, 2020, 154 x 154 cm

-

At the time, the presence of women was rather rare in the artistic field. How did you experience these years of training alongside artists such as Farid Belkahia, Mohamed Chebaâ or Mohamed Melehi?

I was very lucky to live this experience at the School of Fine Arts in the 1960s. In my early years, the training was academic and then came the period of research on the contemporaneity of our heritage. "It was the Bauhaus in Morocco. Pupils and teachers worked together in the study of shapes, geometry and colors. The decorations of Berber carpets, traditional embroidery, ceramics and jewelry were at the heart of our experiments. We traveled to the south (Anzi ceilings) and north of the country and mounted public exhibitions in order to raise awareness of abstract painting. We developed new directions and experimented with new things such as skin.

Teachers and students worked in complementarity generating an emulation of great plastic and intellectual richness.

-

Sans tire, 2020

-

Engraving has taken an important place in your life. What attracted you to this technique? What did you find different through this practice (especially compared to painting)?

In 1978, I was invited, with others, to do a mural painting in the streets of the city, during the 1st International Art Festival of Asilah (Moussem of Asilah).

There, I discovered engraving through the teaching of the great master engravers who are Mohamed Omar Khalil, Robert Blackburn and Hector Saunier. Attracted by this discipline that I consider as a major art, I continued to train and become passionate about the many techniques that it offers. I went to New York and Paris to learn the subtleties of copper, zinc and wood engraving.

Since then I have been participating and leading Assilah's engraving workshop. It's been 40 years!

-

The seaweed pattern is recurrent in your work. Why is this?

The seaweed arrived by chance, while drawing ...

Then, I became interested in form, its multiplicity and the possibility of declining it ad infinitum. Algae also appears to me as an essential element to life. The dictionary of symbols gives this definition: "Immersed in the marine element, reservoir of life, algae symbolizes a life without limits and that nothing can destroy, elementary life, primordial food".

Through the gesture of my hand, the seaweed takes different forms that historians and critics associate sometimes with the female body, sometimes with the cells that multiply or even with calligraphic scrolls. The addition of color brings a kinetic dimension that interests me a lot.

-

You conducted the engraving workshops during the Moussem of Asilah for many years. How was this personal investment important to you? Do you see it as a continuity of the ideas defended by the Casablanca School movement?

For me, it was a kind of continuity of the spirit of the School of Fine Arts. The same great artists participated in it. Mr. Minister Mohamed Benaissa and the painter Melehi have worked hard to ensure that this cultural Moussem, unique in the world, evolves and is known nationally and even internationally. The greatest artists, painters and engravers from all over the world were there and are still invited. Exchanges, conferences, dialogues were enriching and full of messages for the young artists.

-

To go further

-

Available works of art